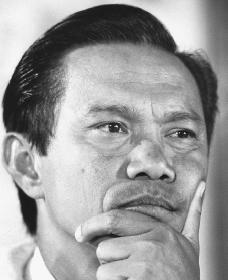

Dith Pran, the Cambodian-born journalist whose harrowing tale of enslavement and eventual escape from that country’s murderous Khmer Rouge revolutionaries in 1979 became the subject of the award-winning film “The Killing Fields,” died Sunday. He was 65.

Dith died at a New Jersey hospital Sunday morning of pancreatic cancer, according to Sydney Schanberg, his former colleague at The New York Times. Dith had been diagnosed almost three months ago.

Dith was working as an interpreter and assistant for Schanberg in Phnom Penh, the Cambodian capital, when the Vietnam War reached its chaotic end in April 1975 and both countries were taken over by Communist forces.

Schanberg helped Dith’s family get out but was forced to leave his friend behind after the capital fell; they were not reunited until Dith escaped four and a half years later. Eventually, Dith resettled in the United States and went to work as a photographer for the Times.

It was Dith himself who coined the term “killing fields” for the horrifying clusters of corpses and skeletal remains of victims he encountered on his desperate journey to freedom.

The regime of Pol Pot, bent on turning Cambodia back into a strictly agrarian society, and his Communist zealots were blamed for the deaths of nearly 2 million of Cambodia’s 7 million people.

“That was the phrase he used from the very first day, during our wondrous reunion in the refugee camp,” Schanberg said later.

With thousands being executed simply for manifesting signs of intellect or Western influence, even wearing glasses or wristwatches, Dith survived by masquerading as an uneducated peasant, toiling in the fields and subsisting on as little as a mouthful of rice a day, and whatever small animals he could catch.

After Dith moved to the U.S., he became a goodwill ambassador for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and founded the Dith Pran Holocaust Awareness Project, dedicated to educating people on the history of the Khmer Rouge regime.

Schanberg described Dith’s ordeal and salvation in a 1980 magazine article titled “The Death and Life of Dith Pran.” Schanberg’s reporting from Phnom Penh had earned him a Pulitzer Prize in 1976.

Later a book, the magazine article became the basis for “The Killing Fields,” the highly successful 1984 British film starring Sam Waterston as the Times correspondent and Haing S. Ngor, another Cambodian escapee from the Khmer Rouge, as Dith Pran.

The film won three Oscars, including the best supporting actor award to Ngor.

“Pran was a true reporter, a fighter for the truth and for his people,” Schanberg said. “When cancer struck, he fought for his life again. And he did it with the same Buddhist calm and courage and positive spirit that made my brother so special.”

Dith spoke of his illness in a March interview with The Star-Ledger of Newark, N.J., saying he was determined to fight against the odds and urging others to get tested for cancer.

“I want to save lives, including my own, but Cambodians believe we just rent this body,” he said. “It is just a house for the spirit, and if the house is full of termites, it is time to leave.”

Dith Pran was born Sept. 27, 1942 at Siem Reap, site of the famed 12th century ruins of Angkor Wat. Educated in French and English, he worked as an interpreter for U.S. officials in Phnom Penh. As with many Asians, the family name, Dith, came first, but he was known by his given name, Pran.

After Cambodia’s leader, Prince Norodom Sihanouk, broke off relations with the United States in 1965, Dith worked at other jobs. When Sihanouk was deposed in a 1970 coup and Cambodian troops went to war with the Khmer Rouge, Dith returned to Phnom Penh and worked as an interpreter for Times reporters.

In 1972, he and Schanberg, then newly arrived, were the first journalists to discover the devastation of a U.S. bombing attack on Neak Leung, a vital river crossing on the highway linking Phnom Penh with eastern Cambodia.

Dith recalled in a 2003 article for the Times what it was like to watch U.S. planes attacking enemy targets.

“If you didn’t think about the danger, it looked like a performance,” he said. “It was beautiful, like fireworks. War is beautiful if you don’t get killed. But because you know it’s going to kill, it’s no longer beautiful.”

After Vietnamese forces invaded Cambodia in 1979 and seized control of territory, Dith escaped from a commune near Siem Reap and trekked 40 miles, dodging both Vietnamese and Khmer Rouge forces, to reach a border refugee camp in Thailand.From the Thai camp he sent a message to Schanberg, who rushed from the United States for an emotional reunion with the trusted friend he felt he had abandoned four years earlier.

“I had searched for four years for any scrap of information about Pran,” Schanberg said. “I was losing hope. His emergence in October 1979 felt like an actual miracle for me. It restored my life.”

After Dith moved to the U.S., the Times hired him and put him in the photo department as a trainee. The veteran staffers “took him under their wing and taught him how to survive on the streets of New York as a photographer, how to see things,” said Times photographer Marilynn K. Yee.

Yee recalled an incident early in Dith’s new career as a photojournalist when, after working the 4 p.m. to midnight shift, he was robbed at gunpoint of all his camera equipment at the back door of his apartment.

“He survived everything in Cambodia and he survived that too,” she said, adding, “He never had to work the night shift again.”

Dith spoke and wrote often about his wartime experience and remained an outspoken critic of the Khmer Rouge regime.

When Pol Pot died in 1998, Dith said he was saddened that the dictator was never held accountable for the genocide.

“The Jewish people’s search for justice did not end with the death of Hitler and the Cambodian people’s search for justice doesn’t end with Pol Pot,” he said.Dith’s survivors include his companion, Bette Parslow; his former wife, Meoun Ser Dith; a sister, Samproeuth Dith Nop; sons Titony, Titonath and Titonel; daughter Hemkarey Dith Tan; six grandchildren including a boy named Sydney; and two step-grandchildren.

Dith’s three brothers were killed by the Khmer Rouge.

I never had the opportunity to meet him, the closest I ever came was winning second place last summer in the AAJA sponsored Dith Pran photo shootout.

We lost an icon today.