As journalist, our stories go into the paper and inform the public today, but in time it becomes history and if that history is built on lies, then we become a nation of lies.

But how do we define truth and when does something become truth? We once believed that using leeches as a medical remedy was a truth. Weapons of mass destruction were sold as a truth. Up to a few weeks ago scientist had to re-examine the truth of dark matter.

I don’t have a simple answer to this, this is just the type of fascinating stuff that I like to think about (other topics include: How is memory stored in the brain, will nano technology lead to cameras we can wear over our eyes and fire by blinking and how do they get those widgets into cans of Guinness?)

I think it’s important to think about these things, especially as journalist we have a gatekeeper’s responsibility to ask the sometimes rude questions and pursue every angle so that truth will emerge.

We have no other choice but to get it right and get it right the first time, and if you think otherwise, perhaps you should look into another line of work. For one, fiction pays more.

War and Truth is a recent documentary that looks into the history of war, from WWII to today and examines the way we cover it, what our government controls and how truth and history is shaped by these actions.

War and Truth is a recent documentary that looks into the history of war, from WWII to today and examines the way we cover it, what our government controls and how truth and history is shaped by these actions.

And unlike Fahrenheit 9/11 or OutFoxed or Fahrenhype 9/11 it tries to do so in a balanced approach where truth is paramount and no judgment is made on the part of the film. (Also see Why we Fight, Fog of War and Capturing the Friedmans if you’re into good journalistic documentaries done right.)

And it doesn’t pull any punches: “If people are going to vote for war and we are gonna put this nation at war, we ought to know something about it,” says Roger Peterson, former ABC corespondent who was seriously injured in Vietnam, in the film. (Bonus: Ted Koppel name drops him in this excellent speech to the Overseas Press Club.)

The focus of the film is journalist and how war is covered. They speak with journalist from every era and from all sides, from the mainstream free press to the internal military press. It also asks why this is important, for journalist to take such large risks to do the job. According to Committee to Protect Journalists 112 journalist have been killed in Iraq as of today (10 more since the May 07 statistics the film uses).

There has to be a reason why we do this.

One more thing, Helen Thomas is a firecracker. I’ve never felt compelled to reference the 40s and call anyone a “fire cracker” before, but there you are. She’s a firecracker.

Other’s have also examined the essence of truth.

Steven Colbert (yeah like his ego needs a link) has made a career out of coining words like truthiness.

The Washington Post’s Baghdad bureau chief Rajiv Chandrasekaran wrote all about his struggle to report on Iraq in the book “Imperial Life in the Emerald City.”

Sig Christenson of the San Antonio Express-News recently wrote a commentary on his struggles and frustrations with both sides, but in particular he takes journalist to task for not asking those tough questions and questioning the given truths.

Last week I was listening to NPR and tuned into to an engaging hour with Paul Watson, and his story of the 1994 Pulitizer Prize winning photograph (warning, the image is very graphic, otherwise I would not be linking to it instead of posting it) of a dead American soldier being dragged through the streets of Mogadishu,Somalia that still haunts him.

I can’t mention everything, but one thing in his story what struck a cord was his reality of what images the Pentagon, wire services and newspapers would allow and reject and thus in turn how this would shape the history of events. In once instance he moved some images of American soldiers whose body parts were being flung about, they didn’t run but the word was out and questions were being asked. According to Watson, the Pentagon denied it as truth and claimed it never happened, in turn this became the new truth of the events.

I can’t recommend it enough, you should give it a listen, it’s very good.

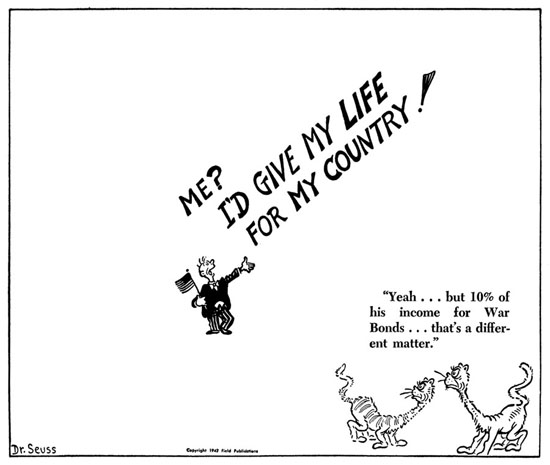

Even Dr. Seuss was shaping the message as a political cartoonist for New York City’s tabloid magazine “PM” during WWII.

Dr. Seuss may be a surprise, but it shouldn’t be. Political cartoonist are often at the forefront of challenging norms and asking the tough questions.

Its a topic Professor Dennis Dunleavy has been examining in relation to the current war. In his research (which I guess he hasn’t published yet) he’s found that in the case of Iraq and in particular Guantanamo Bay, it was the daily newspaper cartoonist who were challenging our excepted truths.

The nature of truth is a very delicate balance. As journalist we are taught to inform and present our findings without any sign or hint of an opinion. There’s a very obvious reason for this, one that I hope should be very clear and evident by now.